History in the making: Celebrating Indigenous History Month

To mark National Indigenous History Month we are exploring the ancestral roots of some Indigenous tourism entrepreneurs and the ways in which our ancestors, our roots and the land influence the ways we move forward in the world. Stories by Lysandra Nothing. Photos by Joe Stephenson.

Great-great-grandfather’s leadership and resistance to colonialism inspires entrepreneur today

Lauren Moberly of Fallen Mountain Soap

Lauren Moberly, owner of Fallen Mountain Soap in Grande Cache, Alta., aims to gently educate people on the history of the land in the nearby Jasper Valley through her business that offers beauty products that are made from the land. At the same time, she continues to blaze the trail of great-great-grandfather, who is known as an explorer, founder and businessman of the Jasper Valley region and became well-known for his resistance to colonialism.

Moberly is a descendent of the families who were evicted from their traditional homes in 1907 as the boundaries of Jasper National Park were drawn. The experience still plays an important part of her family’s history, particularly because her great-great-grandfather Ewan Moberly was a central player in the event.

Prior to the eviction, and despite being illiterate in English and having no formal education, Ewan Moberly was successful in the colonial economy of the Jasper and Grande Cache areas. The Moberly family established roots on a 12-acre homestead, nicknamed the Moberly House, which still stands today within the Jasper National Park. Alongside his brother, John Moberly, Ewan took over the fur trading in Jasper after the Hudson’s Bay Company left for good in 1884.

“Ewan was a very successful businessman, farmer, trapper, guide and explorer with the Jasper region,” shares Moberly.

The Moberly family still shares the story of her grandfather discovering the famous Miette Hot Springs, which today is a popular tourist destination in Jasper National Park. “My family’s story is completely absent from any historical depiction,” says Lauren Moberly.

Ewan’s success meant that he was part of the negotiations that led to the formation of Jasper National Park. Despite his resistance, the government forced the families out of the park, sometimes escorted by the North West Mounted Police. Lauren Moberly’s family history remembers an oral promise that the displaced families would be free to live a traditional life outside of park boundaries.

“(Ewan) was the person that led the people to Grande Cache out of Jasper after trying numerous times to stay in Jasper,” Lauren says. “He led a group of families to Grande Cache because he knew there was good hunting.

“My family’s story is quite interesting and many members of my family have played an important role in shaping the Jasper and Athabasca valley. The effects of the forced removal can still be felt today.”

Lauren and her family continue to live on and off the land left behind from her ancestors.

“Grandpa lived his life the way he wanted to and because of that, myself and my family still reside on the traditional lands he chose to make home after the Jasper eviction.

“I’m so grateful to my grandfather for being the voice for my family and community. Without grandpa, our family and community would be very different today.”

From her own grandfather, Moberly learned to live her life without fear or hesitation. When it comes to hardships, Moberly reflects on her grandfather’s life and finds inspiration to carry onwards.

“Our traditions are starting to be forgotten but that is the other reason why I started Fallen Mountain Soap. I just want to bring back those traditions that I grew up with.

“Indigenous tourism is the future. It is essential to share our traditions and keep those traditions alive, to keep our language alive in our stories.”

Grandparents inspire contemporary Cree artist to carry family traditions through his artwork

Jason Carter of Carter-Ryan Gallery

Stepping into the Carter-Ryan Galleries in Banff and Canmore may seem like a long way from traditional Indigenous art that goes into creating a pair of moccasins. The walls are hung with bright, vibrant paintings with bold colours and strong lines. The sculptures are sleek and modern.

But Jason Carter, the Cree artist behind this work, says he sees himself working directly in the tradition of his grandparents.

“The two of them really made their living as artisans,” said Carter of his grandparents, who created moccasins, jackets and beadwork. “My grandfather was also a woodworker and he built cabins, teepees, and sleds with his hands.”

As a painter and carver, Carter honours his heritage by expressing gratitude to his grandparents for forging the pathway he now walks as an artist.

“My grandparents have passed on now, but it just means a lot to me to be able to share that history,” he says. “I hope they’re proud of me, wherever they are.”

Carter says his grandparents’ connection to the land allows him to create artwork in a meaningful way that builds on that connection. Although his artwork may appear to be in a style much different than his grandparents worked in, the connection to land that his grandparents displayed in their art is impossible to miss in Carter’s work. Much of his work is built around the land around where he now lives — the soaring peaks and craggy nooks of the Canadian Rockies of Canmore, Kananskis and Banff National Park in Alberta.

And Carter also gets to share his work internationally. With galleries in both Canmore and Banff, plus public art displayed throughout Alberta, including prominent works in both the Calgary and Edmonton international airports, Carter says it’s a pleasure to share his culture with an international audience.

“Indigenous tourism is very important to connect everybody, to show that we’re all in this together at the end of the day,” he says. “We’re all really one people.”

Artist and curator finds a sense of identity and culture through grandparents’ teachings and art

Lana Whiskeyjack of Whiskeyjack Art House

A sense of identity goes beyond first and last names. For Lana Whiskeyjack, co-owner and curator of Whiskeyjack Art House located in Amiskwaciy (Edmonton, Ab), her identity is tied to her family’s history and her connection to the land.

Whiskeyjack recalls the story of how her original last name, kwêskácahk, was changed to a colonial version: Whiskeyjack. Due to the difficult pronunciations, name changes were common for many Indigenous Peoples throughout Canada, forever changing their self-identity.

Despite that, the English name became an important part of her and her family’s lives. So much so that, on the 50th wedding anniversary of her grandparents, Whiskeyjack recalls an important conversation with her grandmother.

“She just really wanted me to promise to never get married but I said I couldn’t promise that, but I promise to never change my last name,” she says.

Keeping the name maintains a family matriarchal connection, Whiskeyjack says. “My family endured so much grief and loss, but also power, skills and stories that are connected to our name.” Whiskeyjack honours that promise to this day.

“It is important to care for our grandmothers. I’m grateful that we’re able to continue carrying the name.”

Whiskeyjack is originally from Saddle Lake Cree Nation from Treaty Six territory, but she received a beautiful teaching during her upbringing: she is from this land, not a place with a name.

“Our Cree creation stories tell us especially that we’re free,” she says. “Our spirit came from the cosmos and the heavens, we’re made of four parts of the earth.”

Whiskeyjack says she has a role and responsibility to reconnect to the teachings of her culture and the land. She aims to maintain the connection to both.

“Edmonton is a gathering place for many of our nations and it’s important that we come together and build those relations (between teachings and the land).”

Whiskeyjack Art House is a testament to her passion for reconnecting to her culture and teachings.

Whiskeyjack is passionate about Indigenous tourism because it provides opportunities of connection and understanding.

“Bringing practices of kindness, sharing, being honest and courageous are principles into creating good relations through Indigenous tourism,” she says. “Indigenous people carry so many beautiful teachings, traditions and stories of this land that the rest of Canada and visitors to these lands can learn, and build a healthier relationship with the land.”

Entrepreneur’s Indigenous business inspired by famous father’s groundbreaking career

Samaria Cardinal of Mystical Metis

As a daughter of a renowned Indigenous architect, Samaria Cardinal, owner of Mystical Métis, finds herself inspired by her father’s career, an inspiration that paved the way for Cardinal to pursue her own journey to educate and reconcile with non-Indigenous peoples.

“His whole career was showing the world that an Indigenous architect can do the job and do it beautifully and do it right,” says Samaria.

Born in Calgary, Samaria’s father Douglas Cardinal grew up in the Porcupine Hills of Alberta. As a child, he was forced to attend a residential school. After this very dark period of his life, he pursued his passion for art and found himself aiming to become an architect. Cardinal enrolled at the University of British Columbia with excitement, but the excitement would prove to be short-lived. Within six months, Douglas left the program.

“He was not of the right family background and his designs were very organic that weren’t en vogue at that time,” explains Samaria.

Despite the unexpected setback from the program, her father was still passionate about his dreams.

“He didn’t want his dreams to go out the window so he decided to get into another university.”

Inspired by the way famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright incorporated nature into his designs, Douglas headed to the U.S. with the intention of studying with him. Douglas ended up graduating from the University of Texas at Austin and then headed back to Canada.

“He was very very happy to get his degree and come back to Red Deer,” recalls Cardinal.

A Catholic priest named Father Marks gave Douglas Cardinal his first building: St. Mary’s Church. The roof Douglas envisioned, however, seemed impossible to build because of limitations in technology at the time.

“He had to get a computer from the University of Texas in the ’60s and it cost $750,000 to build the computer, which has less data and processing than our phones currently do,” says Samaria. “But with this computer, they were able to make the calculations for the roof.”

When the church was completed, her father joked that the devils could hide in the corners, because the architecture of the church included sleek curves and tight corners.

From there, Douglas’s career blossomed, and he became known around the world for his designs, which includes the Canadian Museum of History in Ottawa, the Edmonton Space Science Centre and the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, D.C., among countless other buildings.

“All of his buildings conform to the teachings he was brought up with,” says Samaria. “When you look at them, the sun hits during solstices at certain times. He likes to build out of rocks from the Earth and often shapes his buildings in a very feminime form.”

Samaria says her father valued contributing back to the community where he was raised.

“He suffered a lot of racism,” says Samaria, “So it’s very important to him to advocate for Indigenous People.”

Beyond his achievements as an architect, he became a leader for Indigeous Peoples. He was involved with the movement around the Red and White Papers with Harold Cardinal Steiner, in which Indigenous Peoples asserted their treaty rights with the Canadian government. Her father was also part of the movement that convinced owners of the Major League baseball team in Cleveland, Ohio to change its racist name and logo.

“He impressed me because I was brought up with the idea that we can do anything that we want to do as Indigenous people and we can overcome the trauma, we can overcome the racism, and we can show the world how beautiful we are,” Samaria says.

Today, Samaria practices the same principles in her own business promoting and selling Indigenous art through her business Mystical Metis in Calgary.

“My father had his own business his whole life and showed the world our beautiful culture, who we are, and what we have to offer,” she says. “So for myself, I have my own business and it’s really important to showcase to the tourists who we are to break down the barriers and to gain understanding through education and open arms.”

By creating a learning environment, Cardinal hopes to lessen the bias and racism towards Indigenous People and to show tourists that Indigenous People have a beautiful culture.

“(Indigenous tourism) breaks down the barriers and creates understanding.”

The power of family: Uncle’s impact creates a stronger connection to the land and Indigenous way of life.

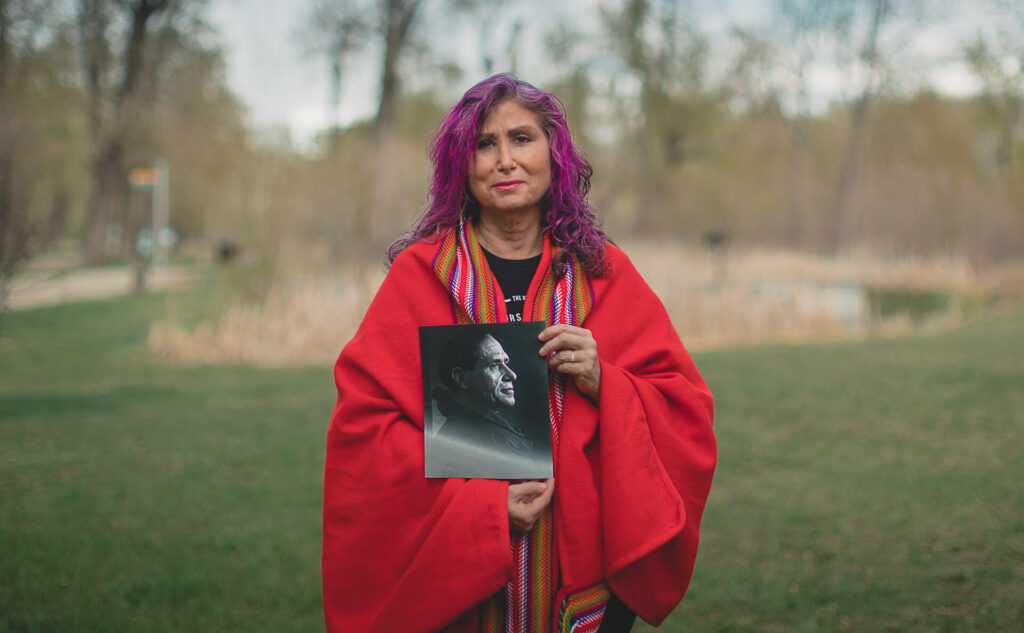

Matricia Brown of Warrior Women with Uncle Joe Chowlace

Matricia Brown is passionate about sharing her Cree culture with travellers to Jasper through her acclaimed company Warrior Women. But she didn’t start connecting to her own culture herself until she met her uncle as an adult.

Brown grew up disconnected from her biological family and her culture, until her Uncle Joe recognized her mother’s facial features in her, and knew immediately that they were related. Upon introduction, the two established a meaningful relationship from which Brown would learn Indigenous ways of life and traditions.

“Uncle Joe is somebody that I met later in life in my early 30s,” shares Brown. “He gave me a lot of teachings. He taught me how to drum songs, how to prepare fish.”

Brown recalls her Uncle Joe writing poems and stories that were eventually gifted to her. Even stronger are her memories of her uncle as a great fisherman.

“He often netted big fish down at Long Lake, and he taught me how to prepare them in an Indigenous way and smoke them,” shares Brown. “I’m really happy that Uncle Joe came into my life for a brief time, simply because it allowed a connection to my original family. It allowed me to identify as an Indigenous person in a different way.”

Brown was equally happy to connect with someone who spoke her traditional language.

Those family connections to the land are now a fundamental part of Warrior Women. In addition to offering singing and drumming performances, workshops and guided tours, Brown offers medicine and plant walks, which teach travellers about traditional plants and medicines and cultural connections to the land that she started learning through her uncle.

“I look through an indigenous lens and teach people the medicinal values of those plants and trees and roots,” she say. “I’m passionate about Indigenous tourism because it allows us to tell our story through our voice in an authentic way.”

From family to the mountains: the legacy of her grandma’s teachings shapes Indigenous tourism company.

Heather Black of Buffalo Stone Woman with grandmother Susie Hunt Daychief

Every family has its own traditions, but for Heather Black, family is more than just traditions. It’s a legacy she carries and honours today.

Black is the owner and founder of Buffalo Stone Woman where individuals can book unique “Indigi-scape” tours in the Rocky Mountains to hike trails that are dotted with beautiful scenery. It’s her family’s connection to the land, however, that remains the guiding light for her business.

Black recalls her grandmother, Susie Hunt Daychief, as someone who was humble and taught many principles that Black still carries close to her today.

“Everything about her nature is instilled in me,” shares Black.

Daychief taught her the traditional ways of making a place a home, how to look after children, and how to support them as they grow.

“Anything she does is traditionally rooted,” said Black, who says her roots in a family of hunters gives her a deep connection to the land close to her heart.

“My grandmother was a huge teacher to all of us. She taught us that the men are the hunters and the women are the meat-cutters. So we’ve learned how to cut the meat, utilise all the animals for different dishes and all of that.”

Black’s grandparents only shared stories in Blackfoot as a way of closing the growing gap in language and culture, which were being lost.

“I look back today and it’s up to me as an individual to really embrace the teachings from my grandparents, from my father, from my aunties, and from all of the Elders and knowledge keepers who are willing to share those stories with us.”

Black’s grandparents believed in the importance of learning their language and to continue on their own individual journey to forge connections with the land.

A combination of Black’s adventurous personality and her grandparents’ teachings enables her to provide numerous hiking tours through her business. But more than that, it is her connection to the land that inspires her to share her Indigenous culture through tourism.

“Being an adventurer also means being connected to the land,” she says. “It means learning traditional ways of how we used to eat and hunt, all of these things is what connects me to the mountains.”

Additionally, Indigenous tourism allows Black to share stories of resilience.

“We all carry our stories of resilience. We all have so many stories to share, and it’s those stories of resilience that provide authentic Indigenous tourism.”

“Our connection to the land is forever.”

Grandparents instilled sense of food sovereignty into chef

Scott Iserhoff, of Pei Pei Chei Ow, with grandparents Louis Shisheesh and Bernadette Shisheesh

Louis Shisheesh and Bernadette Shisheesh taught Scott Iserhoff the importance of food sovereignty in Indigenous culture: energy transfers into what you create.

Iserhoff, a chef who blends traditional and modern Indigenous cuisine, brings these ideas to life through his company, Pei Pei Chei Ow.

“They really raised me up around traditional food and to really appreciate and respect the food that was given to me,” says Iserhoff who notes that one of the valuable lessons he learned was to not cook when he is angry.

At Pei Pei Chei Ow, the menu is inspired by the land, life and seasons that surround today’s world.

Food sovereignty is a concept that Iserhoff hadn’t considered until he began to understand the importance of food and the journey of food from the land to the plate.

“Food sovereignty means culturally appropriate food and eating where you’re from, from the land,” he says. “Food sovereignty is having the ability to buy what you want, decide what you eat but also being healthy as well.”

For Isheroff, thinking about food memories brings him back out to the land. One of his very first food memories includes sitting around a fire inside a teepee and smoking fish.

“Being out on the land is medicinal,” said Iserhoff, recalling memories of running wild as a kid on the land.

“Society likes to push kids to do stuff like get good grades, but (my grandparents would) always just take us to the land and just sit down with tea and bannock and just have fun,” he says.

“The memories of my grandparents really keep me grounded as an individual,” shares Iserhoff, who considers himself lucky to have grandparents who shared a special commitment to each other, a value that is not so commonly seen today.

Iserhoff says the good memories with his grandparents gifted him the privilege of sharing stories through the food.

When it comes to Indigenous tourism, Iserhoff believes that it is something the world should know.

“The more Indigenous tourism there is, the more representation across Canada there is,” says Iserhoff.

“We’re different from nation to nation, people to people, with different stories.”

Isheroff points out the way Indigenous people value the land and resources as well as the way stories are shared are unique.

“There’s always new stories coming out, there’s new legends out there, and there will be new legends.”

Iserhoff believes that Indigenous tourism shows society that Indigenous peoples are not all the same.

“That’s the most important part of what I do, with what our business does.”

To mark National Indigenous History Month we are exploring the ancestral roots of some Indigenous tourism entrepreneurs and the ways in which our ancestors, our roots and the land influence the ways we move forward in the world. Stories by Lysandra Nothing. Photos by Joe Stephenson.

From fighting alongside Louis Riel to planting deep roots

Yvonne Jobin of Moonstone Creation, with her grandfather Louis

Louis Jobin fought alongside Louis Riel in the last battle of the North-West Rebellion for Metis rights. Two generations later, his granddaughter is keeping his legacy alive in a much different way.

Yvonne Jobin, Louis’s granddaughter, is now the owner of Moonstone Creation, a unique gallery in Calgary that sells authentic Indigenous arts and crafts. As part of our project for National Indigenous History Month exploring the ancestral roots of Alberta’s Indigenous tourism operators as a way of highlighting the importance of identity, connection to the land and passion for tourism, Yvonne is sharing the story of her grandfather.

Louis Jobin planted roots that blossomed into the Jobin family that would flourish from his legacy of teachings and values. Louis Jobin fought alongside Louis Riel in the uprising in Batoche, Sask in 1885. Batoche, a historical Métis community, is where Métis leaders Louis Riel and Gabriel Dumont met their downfall at the hands of Canadian government soldiers.

After the resistance came to an end, Louis Jobin trekked a new journey to northern Alberta and took a land scrip within Peace River country in northern Alberta. Louis Jobin cultivated the land into a farm, located 32 kilometres northeast of High Prairie, which was a predominantly Métis community. The farm would become a homestead for future generations of the Jobin family.

“My grandfather was very smart and innovative, he tried all kinds of different crops, he even tried out sugar beets to see if they would grow in the climate,” says Yvonne Jobin. “He brought the first threshing machine to the Peace River Country.”

Yvonne says her grandfather helped kick-start the dairy industry in Peace River Country, and he quickly adopted a leadership role within the community, becoming part of the committee that founded the first school in Peace River Country.

Over the years, farms surrounding High Prairie were sold and the Métis community slowly thinned. “There are a few Métis families there (today),” reminisces Yvonne.

Yvonne grew up on the mixed farm that became home to horses, cows, pigs and other farm animals. Surrounded by the vast fields, she remembers picking berries and clearing rocks to expand the fields.

“A big part of what we did was gather food for the winter,” she says. “We also picked and identified herbs.” Yvonne carries her family’s knowledge of the land to this day. “It’s just a part of our life.”

The farm is still within the family, despite the family house remaining empty. Yvonne is happy that they can still go back there anytime.

“You know, the connection to the land never really leaves you. I am grateful that I am able to live in the city but I eat wild meat and I have chickens in my backyard.

“My mooshum would be so proud of me.”

Jobin instils the value of teaching and preserving native culture with Moonstone Creation, a store located in the heart of Calgary that creates and celebrates Indigenous artists and art.

“A part of what Moonstone Creation is all about is teaching and preserving the native culture. That’s what we’ve always done. We’re always teaching people who want to know the meanings behind the things we make and our culture,” Jobin says. She loves seeing the excitement people express when they learn about Indigenous culture.

Jobin honours her family’s lineage, acknowledging the strong women in her family who grew alongside her grandfather Louis Jobin.

“I am so grateful that I carry him within my heart and that it’s a part of making me who I am today.”